It happened again last week. My dear manager referred to the “verbiage” in something I’d written for a client.

After two decades as an English professor and editor, after developing or sharpening hundreds of story and book manuscripts, and after marking up tens of thousands of student essays, what I heard in that moment was the linguistic equivalent of nails on a chalkboard.

To be clear, her word choice was not intended to be unkind.

Excessive wordiness—that’s what “verbiage” means. You know, verbal bloat. The kind of fluff that clutters communication and dilutes meaning.

If you work in marketing, communications, or any business environment that involves writing, you’ve probably heard it used incorrectly a thousand times.

- Let’s update the verbiage on the homepage.

- I like the verbiage in this email.

- Can you send me the verbiage for that section of the report?

Corporate America has adopted it as a pseudo-sophisticated synonym for “words,” and it’s often deployed because some people think it sounds more professional. Or perhaps they’re just bored and want to spice up their discourse.

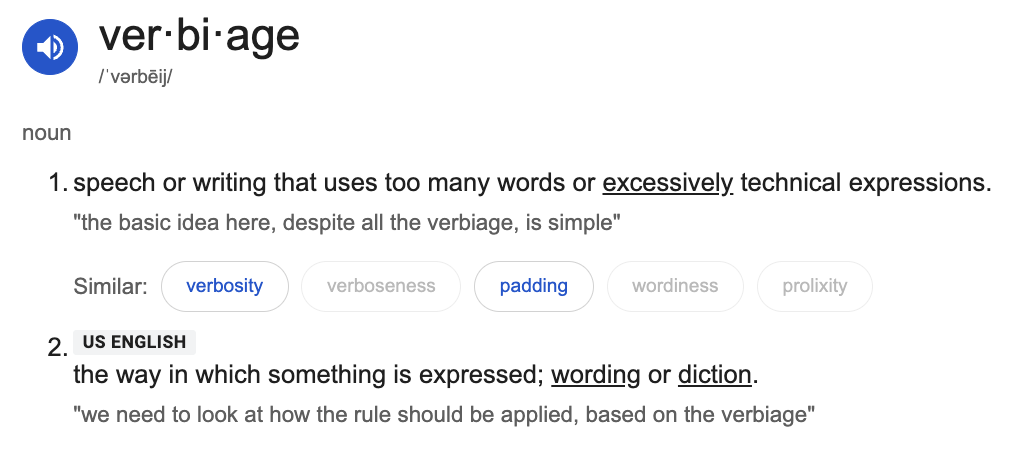

The worst part is that, these days, such usage is not entirely wrong. Search for “verbiage” in most dictionaries and you’ll now find two definitions. The first—the original and correct denotation—defines it as “speech or writing that uses too many words or excessively technical expressions.” You’ll see synonyms like verbosity, wordiness, and padding.

In other words, all the pitfalls good writers want to avoid in their work. But scroll down to the second definition and you’ll see the problematic secondary denotation: “the way in which something is expressed; wording or diction.”

Dictionaries have caved because of its entrenched (mis)usage. But for a language professional, this is yet another battle in the eternal war between documenting how language is actually used and maintaining standards for how it should be used.

Descriptivists will tell you that language evolves. “Dost thou love me?” Juliet asks Romeo in a 16th-century play set in 14th-century Italy. But four centuries later, “Do You Love Me?” (1962) by the Contours reached #3 on the Billboard chart. They’ll also say that usage determines meaning and argue that trying to hold back linguistic evolution is like trying to stop the waves crashing against the shoreline.

These are the same people who say it’s “alright” for “all right” to be spelled as one word. (They’re wrong.)

But prescriptivists—and most professional writers, in my experience—would counter that not all evolution is progress. Before “verbiage” became corrupted, we had a single, clear word that meant “excessive wordiness.” Now we have a word that means both “excessive wordiness” and “the use of words.”

Precision is, like, not a thing anymore or something.

Writers who’ve spent their careers learning to wield language feel that loss acutely. Our toolboxes are being filled with increasingly dull instruments.

Since I’ve drilled down this far, I might as well add that “wordsmith” irks most writers, too. Used as a verb—let’s wordsmith this—it reduces writing to mere tinkering, as if crafting clear, persuasive prose is merely a matter of hammering out words here and there. Used as a noun to describe writers, it sounds cutesy at best and dismissive at worst.

Such terms are the verbal equivalent of stock photography—generic enough to seem professional while still vague enough to avoid meaning anything specific. Good writers don’t just arrange words in a pleasing order. They analyze an audience’s needs. They construct arguments. They manage tone, build credibility, anticipate objections, and make hundreds of strategic decisions that most readers may never consciously notice.

All businesses need real writing and clear communication that builds trust and prompts action. Writers who understand rhetoric know that every comma placement and word choice has the potential to either move the reader closer to the intended goal or push them away.

Unfortunately, writers may have to let “verbiage” go the way of “literally,” but we can still advocate for clear, purposeful communication—regardless of what you call it.

Common for Most Business Settings

- Copy

- Content

- Messaging

- Draft

- Text

- Language

- Wording

- Prose

- Writing

- Phrasing

- Passage

Depending on Context:

- Headline/body copy/tagline (for websites)

- Script (for video/audio)

- Microcopy (for UI/UX writing)

- Caption (for social media)

Used in Sentences:

- “Can you review the copy?”

- “Let’s tighten up the messaging.”

- “This content needs another pass.”

- “I’m loving the language used here.”

- “This passage needs another look.”

Update: Between editing and publishing this post, I received a Slack notification about the “verbiage” on a client’s site not aligning with their privacy policy.

You might also like:

Rare Bird delivers versatile marketing and digital solutions to diverse clientele across nearly every industry. Ready to leverage our expertise to address your business needs?

Let's talk.